What is the gender gap in urban cycling and why is it a key indicator for an equitable and just city? We know that improving cycling infrastructure has become an essential best practice in urban planning – to reduce carbon emissions, to improve health, to slow the city down, to reduce air and noise pollution. But does everyone benefit equally from new bike lanes? If the dominant users are white males, are city investments reinforcing gender inequality? How do we estimate the proportion of female cyclists and bike lane users in a city and what can be done to reduce gender differences? What would a cycling network look like if it were designed by and for women? What types of bike lanes are better for women? If planners were to incorporate a feminist perspective in the design of new cycling infrastructure, what would this look like?

Thinking about gender equity in urban cycling policy and design opens a whole range of questions that urgently need to be addressed to create an equitable and just city.

Often, data on the gender gap in cycling comes from surveys. We ask men and women: do you bike? and maybe we ask how often. This can produce preliminary estimates on the proportion of female and male cyclists.

The problem with surveys is that what people say may not match what people do. Someone can say they are an urban cyclist if they bike once a week or once a month. Or some who bikes for recreational purposes on weekends may not consider themselves cyclists at all.

These problems with the survey data has led me to be a fan of observational counts with field work. In an extensive observation in 2018, we found that in Barcelona the gender gap in 2018 was 2 males per female (2:1) or 34.5% female to 65.5% male (Lind 2018). These are highly reliable estimates because it involved collecting 12,038 observations (!). Furthermore, when breaking down the data by site, the gender gap of 2:1 was strikingly similar across locations, all of which were Barcelona’s Eixample grid.

We found that women were more likely to comply with intersection rules, including stopping on a red light. This means that brining more women into the cycling network is more than merely an issue of equity and justice, but also is likely to create a stronger culture of safety and respect. The research was published in Transportation Letters (Lind et al 2020) and you can listen to a conversation about this paper in the Dense City podcast with Rebecca Meyers (@becmeyers).

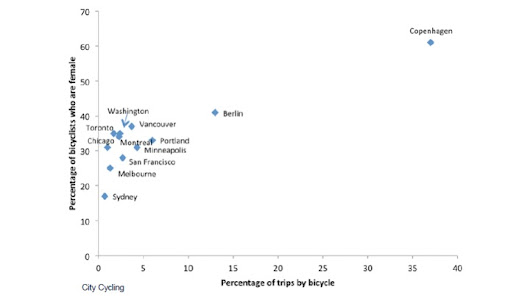

If you examine the gender gap in cities around the world, you can see that as cycling becomes more popular, the gender gap narrows. The exact causal nature of this relationship is unclear, but it is probably fair to say that as a city becomes more bike-friendly more women will bike and at the same time women are the key to help cities more bike friendly. The figure shows Copenhagen as the ubiquitous cycling outlier, with a cycling modal share nearly 40% and over 60% of cyclists are women.

Figure. There is a positive relationship between the a city’s modal share of cyclists (x-axis) and the percentage of bicyclists who are female (y-axis). Source: Unknown.

Now in 2021, I have begun to work with a student from Albörg University, Charlotte Collot, and cycling consultant Esther Anaya (@anayaesther), to design a research project that will produce an updated gender gap figure for the city of Barcelona in 2021. We are also looking at the different types of cycle path designs, with the hypothesis that more protected cycle paths are more likely to have a gender balance. How will the gender gap vary by cycle path design? What will we find when bikes share the lane with motor vehicles and buses? And what is the gender gap among scooter users and other micro-mobility devices? We hope to have preliminary results this spring 2021.

Many feminist planners are pushing for equitable cycling policies. Work by the feminist planners Col.lectiu Punt 6 has documented the extensive verbal abuse and sexual harassment that women cyclists confront when moving about in the city (Col.lectiu Punt 6, 2020). The study relied on workshops and a very large survey (500+) to identify barriers to cycling for women, including the fact that many must move around the city while taking care of others (children or elderly), signalling structural barriers of a patriarchal society that restricts female mobility and their right to the city.

We are going to need lots work to fix the gender imbalances and inequities in urban cycling. It is clear that narrowing the gender gap is a critical pre-condition for a just and sustainable city. Because when more women bike, everyone wins.

References

Col.lectiu Punt 6. 2020. Dones i persones no-binarias en bici. Estudi de mobilitat ciclista en Barcelona d’una perpectiva feminista. http://www.punt6.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/INFORME-FINAL-BICIS_CATALA.pdf

Lind, A. 2018. Intersection dynamics in Barcelona: An observational cyclist study on user types, behaviour and desire lines. Joint European Master in Environmental Studies – Cities and Sustainability. Autonomous University of Barcelona.

Lind, A., J. Honey-Rosés, E. Corbera. 2020. Rule compliance and desire lines in Barcelona’s cycling network. Transportation Letters doi: 10.1080/19427867.2020.180352